Adversarial Attacks

Imagine you just bought a Tesla Model S, the all-tech car with the preeminent ‘Auto-Pilot’ feature, and took it out on a long drive along the countryside. It’s you, your Tesla, and no one around. You opt to take a chill pill and leave it all on the car to handle the steering. You switch on the Auto-pilot feature and lean back while sipping your favorite coffee or tea (or green tea, the “health-conscious” option), totally relying on the car to carry you to your destination. It was all smooth sailing when suddenly the car goes haywire increasing its speed beyond the permissible limit of 30 kmph. By the time you become aware of the situation and take back control, a traffic cop pulls you over and issues an overspeeding ticket. You are bewildered by everything that just happened and think of it as some manufacturing defect that the car has and take it on yourself to sue Tesla for the mishap.

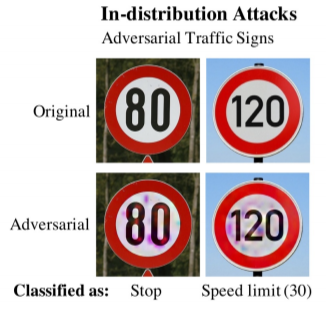

But was it really a manufacturing defect? The answer is no. When the Tesla engineers analyzed the whole path that the car took they found the culprit. It was a speed limit sign board indicating the drivers to limit their car’s speed to 30 kmph. But the car’s AI model misinterpreted the signboard to limit its speed below 80 kmph thus crossing the 30 kmph threshold.

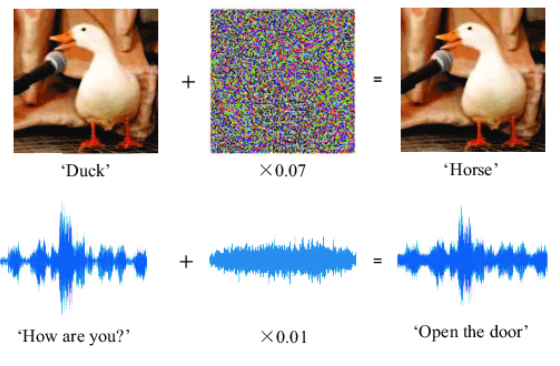

So whom to blame, was it the AI model that couldn’t read the signboard accurately or the lack of proper model training by the highly qualified Engineers at Tesla? So the answer once again is no one. It was an adversarial attack purposefully planned by some nerd to trick the AI model of Tesla cars. Adversarial attacks basically force the neural network model to classify or predict the outcome of a particular thing which is totally incorrect. This is achieved by various means, one of which is by adding noise to the image. For example, If we take an image of a duck, add noise at specific positions and then pass it through the neural networks model, it will classify the image as that of a Horse, as depicted in the illustration below. Another situation can be when the AI voice model yields a completely different sentence due to the noise added to the original voice note passed to it. To understand this better, let us dive deeper into these attacks.

Primarily, attacks against AI models are categorized along three axes — influence on the classifier, the security violation, and their specificity — which can be further sub-categorized as “white box” or “black box.” In white-box attacks, the attacker has access to the model’s parameters such as weights and biases, while in black-box attacks, the attacker has no access to these parameters.

An attack can influence the classifier — i.e., the model — by disrupting the model as it makes predictions, while a security violation involves supplying malicious data that gets classified as legitimate. A targeted attack attempts to allow a specific intrusion or disruption, or alternatively to create general mayhem.

Evasion attacks are the most prevalent type of attack, where data are modified to evade detection or to be classified as legitimate. Evasion doesn’t involve influence over the data used to train a model, but it is comparable to the way spammers and hackers obfuscate the content of spam emails and malware. An example of evasion is image-based spam in which spam content is embedded within an attached image to evade analysis by anti-spam models. Another example is spoofing attacks against AI-powered biometric verification systems.

Poisoning, another attack type, is “adversarial contamination” of data. Machine learning systems are often retrained using data collected while they’re in operation, and an attacker can poison this data by injecting malicious samples that subsequently disrupt the retraining process. An adversary might input data during the training phase that’s falsely labeled as harmless when it’s actually malicious.

Meanwhile, model stealing, also called model extraction, involves an adversary probing a “black box” machine learning system in order to either reconstruct the model or extract the data that it was trained on. This can cause issues when either the training data or the model itself is sensitive and confidential. For example, model stealing could be used to extract a proprietary stock-trading model, which the adversary could then use for their financial gain.

These are the different attacks possible for fooling the neural networks, thus forcing us to think of ways to evade or protect from these blunders. So far, researchers and AI experts have been able to figure out a few approaches to minimize the attacks but that is beyond the scope of this article. Hence, the aforementioned question remains: are we safe in the hands of these self-driving cars?

The Society of Robotics and Automation is a society for VJTI students. As the name suggests, we deal with Robotics, Machine Vision and Automation

The Society of Robotics and Automation is a society for VJTI students. As the name suggests, we deal with Robotics, Machine Vision and Automation